During my time at Paladin I worked on a game for Blind Ferret Entertainment based on their hit webcomic Looking For Group. It’s been the biggest game I’ve worked on and it was a lot of fun, even though we eventually ran into problems that stopped it from going into full production. I wrote a few blogposts about the proces of turning this comic about a game into a game about a comic.

LFG The Fork of Truth was an ambitious project. It has a ton of lore and a large fanbase. So to deliver something as outsiders that fits into the LFG canon we had to become intimately familiar with its universe. To do that I went through a few important design steps before we could start having discussions about how big the fireballs should be.

The steps below are not a rigid structure but merely the way I prefer doing things, and this process applies just as well on books to films, films to games and whatever else.

Look at the source material

This sounds like a no-brainer, but it is easily the most important part. LFG does not begin and end with the comic – the comic is simply one window into the world of Legarion. So just skimming through the comic and lifting out the good parts is not the way to go about it. Many games about movies take this route and it gives them problems because the two media are fundamentally different in structure.

What I’ve learned from doing a webcomic myself for many years is that the most important part is the characters’ identity. If you have an understanding of how each character would behave normally, all you have to do is put them in a wacky situation and the dialogue will practically write itself. They can never do something out of character because you know them as if they were your friends.

The only one who really has that complete picture is Ryan Sohmer himself, and I was very lucky to be able to talk directly to him. Between that and reading reviews, analyses, comments, looking at concept art and talking it through we tried to gain an understanding of this property that approaches Sohmer’s own.

Find a new angle

Once we had that understanding, we started looking for a fresh new angle. The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape From Butcher Bay is a great example of this. Instead of copying the movie they created a brand new story in the Riddick canon that expands on his backstory and creates context for the things you see in the movies. It opens up a new window into that universe. We treated FoT in the same way.

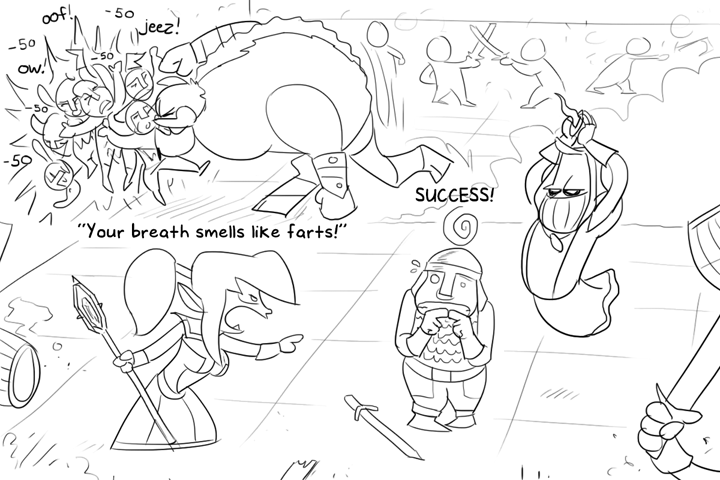

The heroes are always on the move. And we know the high points of their story, from when they met to their trek to Kethenicia, the dwarves, the Plane of Suck, the Legara threat and beyond. But inbetween, what do they do? Where do they get all their fancy weapons and skills? What happens when Richard misplaces his fork during dinner? We aimed to answer those questions, and have players experience the daily life of this group. Which involves a lot of bickering and setting things on fire.

Adapt it to the desired medium

So now that we know our characters and our angle, we start to see how it could fit inside the structure of a videogame. We are in a fantasy world, we have multiple characters with different skills, violent battles and hilarious situations. So logically we end up with a 4-player coop hack-and-slash action-RPG.

During our design process we wrote down these five design tenants, which influence all our decisions:

Make players feel like they are part of the LFG world, not just a random fantasy world – include well-known locations, characters, events.

Give players freedom – within reason, we want players to choose their own adventures.

Pick up and play – players should be able to get into a session quickly and easily.

Multiplayer – the game is focused on playing with friends, though it should not exclude single-player. Playing with others should have benefits to the challenge and the fun.

Quirky crazy humor – If something has potential to be used as a joke, do so. We have to find the twist in every system, the joke in every quest description. If a player hasn’t laughed in 5 minutes, we missed an opportunity.

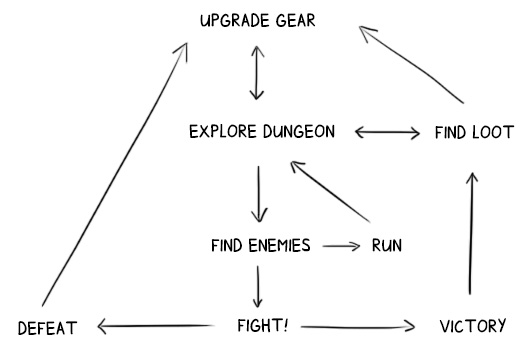

Next we have to start thinking how this actually works. Games are all about repeatable actions, so we design the core gameplay loop, a simple flowchart that shows which things you’ll be doing in the game and how they interconnect:

After that we look at each part of this flowchart and start designing the systems behind them. From the way you travel from dungeon to dungeon to the way the inventory works and what defeat means. I will highlight a few of these ideas in a later blogpost.

Prototype

Then comes the time to start prototyping each of these nuggets. Prototypes are super important to test these ideas before we spend time and money on making them. And once these prototypes feel right we can lock the design and go ahead with the actual production. I’ll talk more about the combat and level design prototypes we made in an upcoming blogpost.